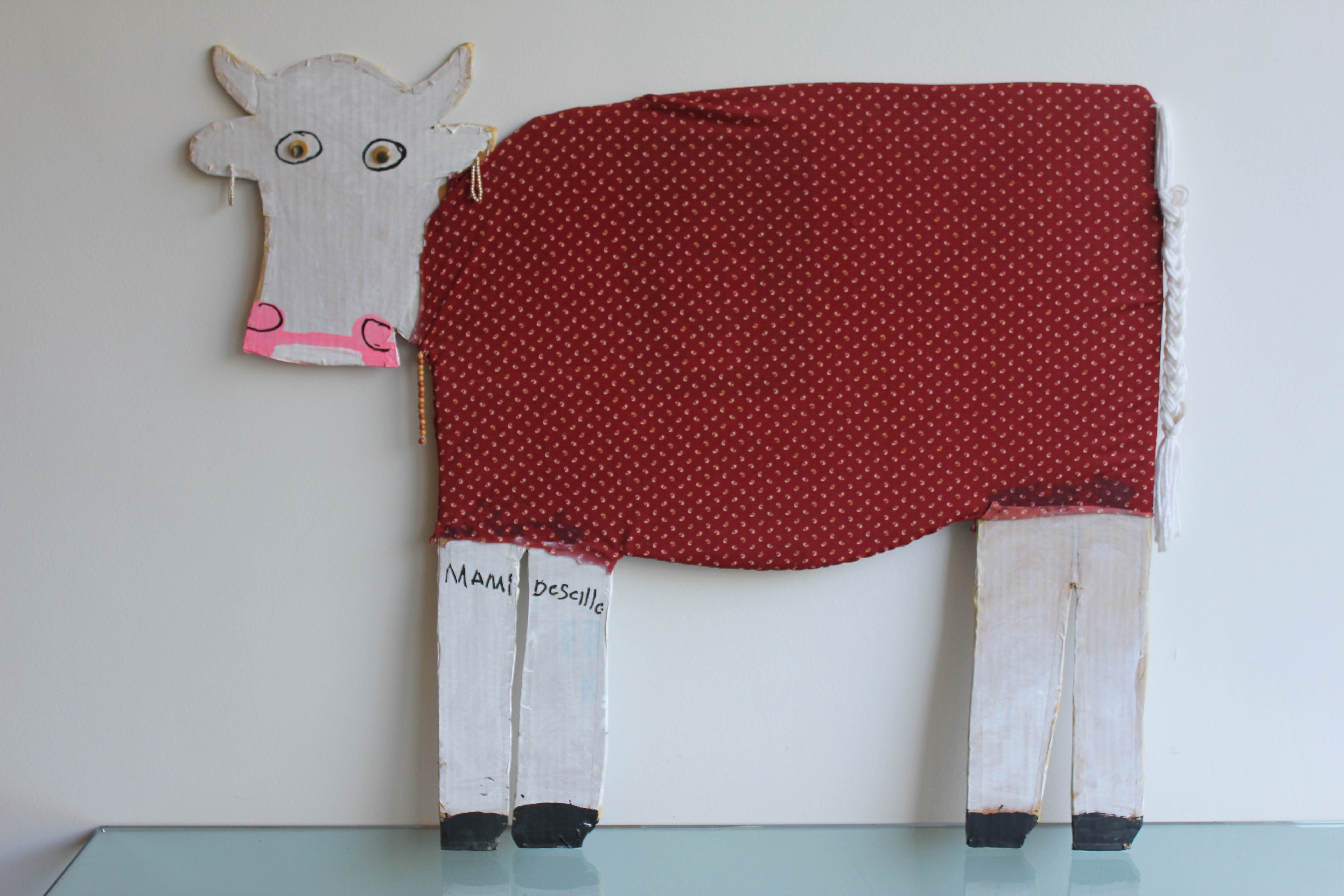

Calf Twin Smaller Dressed

Sheep

Calf Twin Larger Dressed

Spotted Cow

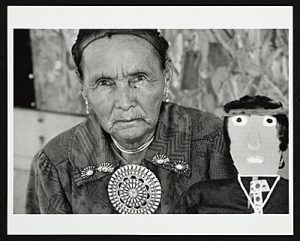

Photo from Smithsonian American Art Museum Website

Friends and family members of Mamie Deschillie remember the woman as an internationally appreciated folk artist who put family first.

Deschillie, a Fruitland woman known as a “folk art superstar,” died Friday in Farmington. She was 90.

Deschillie was an accidental artist, said her daughter, Jane Jones. Deschillie began crafting figures from cardboard and mud after her husband of 39 years, Chee Ford Deschillie, died in 1979, when she was 55.

“She was never one to ask for things,” Jones said of her mother. “She was so proud, strong-hearted, independent.”

Deschillie picked up art as a means to keep her mind busy and her purse full, Jones said. The woman’s media of choice were mud and cardboard, based on traditional “mud toys,” or figures made of sun-dried earth or clay and originally intended as toys for children. Navajo are believed to have used the toys from 1880 to 1940.

Born July 27, 1910, in Chaco, Deschillie attended boarding school through the third grade. She married at age 16 and settled in Burnham, where she wove rugs, herded sheep and raised five children.

Her career as a folk artist began in the 1980s when a pawn shop owner noticed her frequent transactions and collection of old turquoise jewelry and invited her to bring in some mud figures.

Deschillie also painted, made collages and crafted cardboard cutout figures and adorned them with traditional attire and jewelry. The figures have captured the attention and imagination of art and history aficionados far and wide, Jones said.

Deschillie made the figures from cardboard she saved from the Dumpster and adorned with recycled materials or those given to her at art shows. Figures ranged from traditional Navajo people to cowboys riding roosters to circus animals she saw only in books.

Even as her art career blossomed, however, Deschillie continually put her family first, often bragging about its growing numbers. She is survived by two daughters, Jones and Mary Johnson; one son, Jerome Deschillie; 17 grandchildren, 60 great-grandchildren and six great-great-grandchildren.

“She became a grandmother when she was in her 30s,” Jones said. “She was always bragging to the other grandmothers how many grandkids she had.”

Deschillie showed her art throughout the West and eventually gained recognition worldwide for her “true folk art,” said Robb Lucas, manager of Case Trading Post at the Wheelright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe.

Deschillie’s art can be found in many local galleries and museums, the Smithsonian Institution and private collections around the globe, he said.

“She was just a pretty phenomenal individual in terms of Navajo folk art,” Lucas said of Deschillie. “She developed all kinds of new forms with her mud toys and her cutouts and her paintings. It was really true folk art. The art she created came from the heart, the world around her and her imagination.”

Deschillie’s art has a kind of childlike quality, Lucas said.

“She worked with children, and that kind of characterized her art,” he said. “It always had a childlike quality.”

Late in life, Deschillie moved to a horse trailer in Fruitland, south of the San Juan River near Farmington. She worked on her mud and cardboard figures at home, Jones said.

“She made a lot of figures,” Jones said of her mother. “She timed herself once. She could make a mud figure in five minutes, or a whole herd of animals in one day.”

Deschillie was active in the community, serving as president of the Upper Fruitland Senior Citizens Association and volunteering with children.

She is remembered as a traditional Navajo woman who spoke little English and always dressed in velvet, Lucas said.

“We always looked forward to when she visited us,” he said. “She spoke Navajo and we spoke English, but there was communication and we always found her to be a dignified woman, always dressed traditionally with her jewelry. We’re really going to miss her and her art. She was just very unique.”*

*Article from The Daily Times by Alysa Landry

Additional Links:

Smithsonian American Art Museum